05 Feb [Moscow] Mayakovsky square

Period:

1958-1961

Place:

Moscow

Participants:

Yuri Galanskov, Vladimir Bukovsky, Vladimir Osipov, Anatoly Shchukin, Aleksandr Ginzburg, Bulat Okudzhava, Mikhail Kaplan, Apollon Shukht, Vladimir Vishnyakov, Eduard Kuznetsov, Sergey Chudakov, Alisa Gadasina, Alena Basilova and many others.

Description:

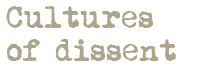

Awaited for a long time, the monument dedicated to Vladimir Mayakovsky by the sculptor Aleksand Kibalnikov, was unveiled on July 28th, 1958 in the homonymous square, that was informally called “Mayakovka”, while today it has returned to its original toponym “Triumfalnaya”. For the occasion, under the statue of the poet, was organized a public reading to which some of the most famous poetic figures of the time took part.

So many people attended the event that at the end of the ceremony some of the bystanders started further readings. In that circumstance the authorities avoided to judge strictly the activity, however in the following weeks and months the situation got out of control. The event, initially conceived and organized from above, turned into a natural general ritual, capable of including figures widely different from a political and artistic point of view: poets, writers, artists (professionals and amateurs). Freedom of expression lovers and simple passers-by found themselves together to declaim poems, written by themselves or by some forgotten poets of the past (avantgarde and modernism works of the early twentieth century were widely required).

That period was the most promising phase of the Thaw, an age of many sincere and shared illusions. The most emblematic figure who attended that common space, also known as “The Lighthouse” (in Russian ‘mayak’), was a young man who hadn’t got excellent poetic gifts; indeed, he is still remembered for his charisma and magnetism, wherewith he was capable of arousing people’s spirits. That man was Yurij Galanskov, author of the poem Chelovechesky manifest (Human manifesto), considered almost a manifesto of ‘Mayakovka’. Still after many years people who attended the readings would not have been able to judge his literary value due to the emotional strength that those lines were able to arouse. Galanskov, the editor of the samizdat almanacs Phoenix (1961) and Phoenix 66 (1966), was considered not only as the catalyst of the Lighthouse, but also as one of the first activists for the human rights in USSR. He died at the age of thirty-three in a labor camp, where he was sent off due to his brave and ceaseless political and literary activity.

Another renowned participant of the evenings in Mayakovsky Square was Aleksandr Ginzburg. Shortly afterwards, he was arrested for printing three numbers of the almanac Sintaksis. As happened to Galanskov and Ginzburg – different figures whose role was equally important – several others habitué of the Mayakovka ended up amid the dissidence rows. Among them we can find Vladimir Bukovsky, Eduard Kuznetsov e Vladimir Osipov.

Afterwards the editor of the magazines Bumerang and Veche, Osipov was even arrested with the allegation of having plot a conspiracy against Khrushchev. It is not clear whether the subversive plot had been contrived by some mayakovtsy or whether it had been a provocation carried out to put an end to the gatherings.

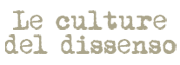

The arranged meetings around the plinth of Mayakovsky’ statue – the poet celebrated by the dictatorship for his role of Revolution bard and revered by the non-conformist youth for his futurist past record and for being naturally rebellious – continued evenly for a few years and greatly upsetting the authorities.

Unable to use violence, in times of feigned tolerance, they attempted several times and, in many ways, to call to order the people concerned. The occasion to put an end to the gatherings arose during the day of the solemn celebrations for Gagarin’s space flight, April 14th, 1961, that was also the anniversary of Mayakovsky’s death. The Lighthouse youth decided to gather in spite of the official ban. The spark, probably instigated by the enforcement officers, broke out in a brawl that embroiled involved dozens of people. Among them there were the several drunks returning from the official ceremony and the officers themselves, who succeeded to arrest Osipov and Shchukin.

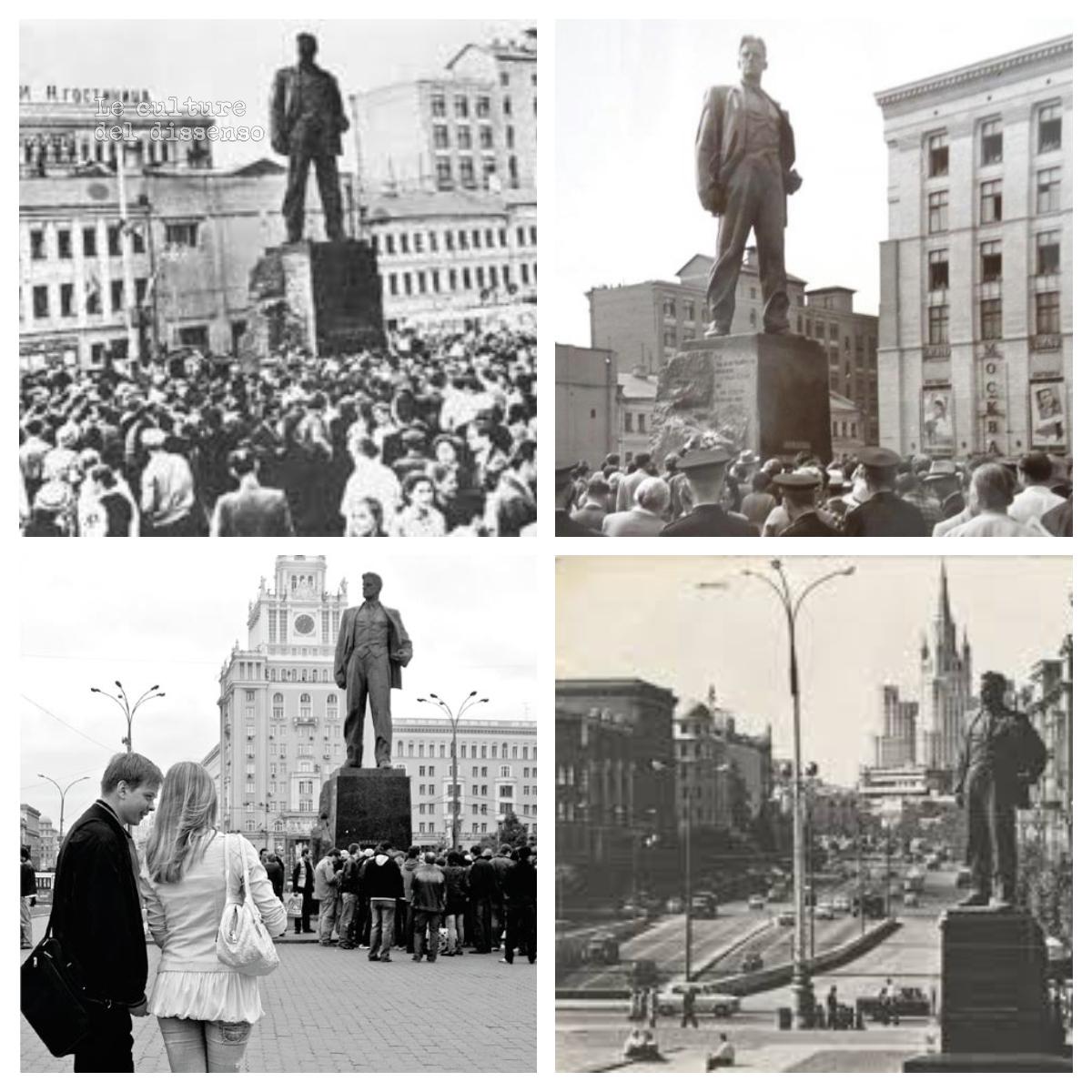

Effectively Mayakovka’s reunions ended that evening, even if the readings would have been going on still for a few months. These young men, who gave rise to such a greatly political experience, although dissimilar from the traditional and contemporary Western forms of protest, later on spill over to private apartments. There they started off a new form of dissent, more intimate and by then devoid of any illusions or changes’ fancy

At the end of an experience that was widely considerable also for the high number of people involved, in the following years the square itself would have become the theater of other types of opposition: for example the artistic and literary protest by SMOG, carried out on April 14th 1965, and the political demonstration carried out by Olga Ioffe and Irina Kaplun: at the same time as Yan Palach’s funerals in Prague the two students showed messages supporting Czechoslovakia. The two young women were arrested and soon afterwards released.

References:

M. Clementi, Storia del dissenso sovietico, Odradek, Roma 2007, pp. 25-32.

I ragazzi di piazza Majakovskij: la poesia alle origini del dissenso in URSS, 1958-65, La Casa di Matriona, Milano 2002.

La primavera di Mosca. Le riviste dattiloscritte sovietiche degli anni ’60: prosa, poesia, impegno civile agli inizi del dissenso, Jaka Book, Milano 1979.

V. Parisi, Guida alla Mosca ribelle, Voland, Roma 2017, pp. 194-200.

G. P. Piretto, Il radioso avvenire: mitologie culturali sovietiche, Einaudi, Torino 2001, pp. 251-254.

G. P. Piretto, 1961: il Sessantotto a Mosca, Moretti & Vitali, Bergamo 1998, pp. 67-69.

L. Polikovskaja, “My predčustvie, predteča…”. Ploščad’ Majakovskogo. 1958-1965, Moskva 1997, http://old.memo.ru/history/diss/books/mayak/index.htm (06/2018).

[Federico Iocca]

[2/9/2019]

[Translated by Diletta Bacci]