23 Jun Phoenix 1966

Period:

1966

Place:

Moscow

Editor:

Jurij Galanskov

Total number of fascicles:

1

Main contributors:

Aleksey Dobrovolsky, Vera Lashkova, Petr Rodzievsky and others.

Description:

Yuri Galanskov started his fight against the soviet regime by redacting in 1961 with other people’s help the sbornik Feniks 1961, because of which diffusion he was arrested and shut up in a mental house.This first non-authorized editorial activity was born in Mayakosvkij Square’s contest; after the unveiling of the futurist poet’s monument the square became a place of aggregation for muscovite youth.

Galanskov was one of the most regular participants of the square: he put his poem-manifesto in Phoenix 1961, that for many people the poem was an unofficial praise of Mayakovsky Square’s gatherings.

The poem, conceived to be declaimed, is like a fundamental element in the auto definition’s process of the poet like a sacrificial victim, as the one who immolates himself in the name of a future universal resurrection. Rebirth’s concept seems to be a solid point in Galanskov’s editorial experience, as shown also by the title Phoenix given to the two collection.

After the arrest and the internment in a mental house, Galanskov went back to his podpol’nyj literator (underground literary man) activity, that is, by his own words: «the one who does secretly his literary activity, as a loyal citizen of his Country and man of honor, and he cannot let the gibes on his country and his minor children go unnoticed».

Exactly for this reason he fixed between his aims that of writing a pacifist magazine; however, after Sinyavsky and Daniel’s arrest, in 1965, he was forced to change his planes: he committed himself in sustaining the arrested, asking for the observance of the Constitution and soviet laws.

The two writers were supported by the organization of the so-called meeting glasnosti, arranged by the mathematician Aleskandr Esenin-Volpin, taking place in Pushkin Square where it was attended by nearly seventy people, and including also Galanskov.

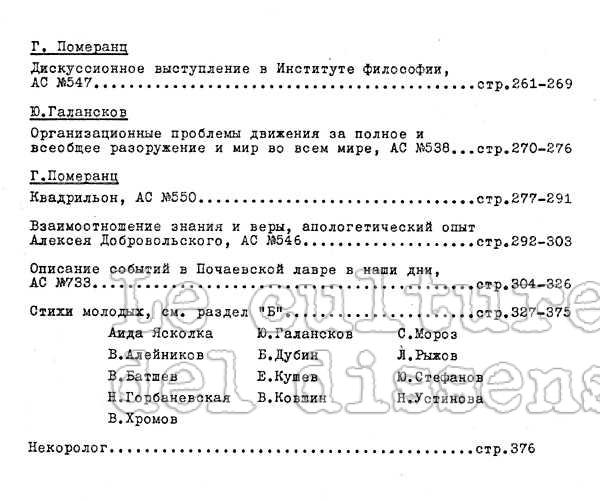

Unlike Phoenix 1961, Phoenix 1966 collects documents typically related to journalism: critical-literary, philosophical, historical, religious and political articles. As Grani’s editorial office said several times, Phoenix 1966 collection had a more considerable political feature compared to other illegal magazines.

In Phoneix 1966 there are essays and documents which were not appreciated by soviet authorities: Galanskov was aware of that, as he admits in the redactional article Možete nacinat’ (You can start). He himself declares the reason of his fight: “You could also win this battle, but you will equally lose this war. The war for democracy and for Russia”.

The texts selected for the magazine seem to outline a critique towards the soviet situation, so that one of the first essays included in it was Čto takoe socialističeskij realism (On Socialist realism) by Andrey Sinyavsky.

Being Phoenix 1966 editor, Galanskov is also author of poems and essays, among them: Otkrytoe pis’mo Šolochovu (Open letter to Sholokhov) and Organizacionnye problemy dviženija za polnoe i vseobščee razoruženie i mir vo vsem mire (Organization of the movement for the whole, general disarming and the peace in the world).

The poet did not simply limit his observations on the Soviet situation, blaming the dictatorial system of the bureaucratic machine and the literary stagnation of the country, but his aim was also the coordination of an international group, that would have as purpose men’s sensibilization related to the disarmament problem.

His humanitarian and honorable personality lead him to manifest several times his disapproval, both in soviet and international field, as shown during many sit-in he carried out in the first half of the Sixties.

Shortly after Phoenix 1966 spread, Galanskov was arrested together with his contributors and just one year after they were sued in the famous “Protzess Chetirekh”.

The four were accused to divulgate anti-Soviet information and Galanskov also to be in contact with Narodnyj Trudovoj Sojuz (Labor Union), based in Belgrade.

Galanskov was convicted under the article 70 to seven years in a forced labor camp in Mordovia, where he died in 1972 due to complications following unsuccessful surgery.

Phoneix 1966 can be considered an example of glasnost’ for two reasons: first of all because Galanskov’s name and address were explicitly written on the magazine, using the procedure already tested by Alik Ginzburg in the almanac Sintaxsis.

Secondly, because the collection is composed of texts that explicitly criticize Soviet situation, identifying the guilty and above all making clear the need to re-establish the constitutional liberties.

References:

[Anonimo], Feniks 1966, «Grani», N° 63, 1967, pp. 3-8.

D. Bacci, Gli inakomysljaščie e la loro eco in Italia: la pubblicazione della rivista non ufficiale Feniks ‘66, Tesi di Laurea, Facoltà di Lingue, Letterature e Studi Interculturali, Università di Firenze, A. S. 2017-2018.

M. Clementi, Storia del dissenso sovietico (1953-1991), Roma, Odradek, 2007, pp. 71-95.

Ju. Galanskov, Feniks ‘66: rivista sovietica non ufficiale, Milano, Jaca book, 1968.

Ju. Galanskov, Sbornik. Samizdat, «Grani», N°89-90, 1973, pp. 143-203.

V. Osipov, Ploščad’ Majakovskovo statj’a 70-aja, «Grani», N° 80, 1971, pp.107-140.

V. Parisi, Il lettore eccedente. Edizioni periodiche del samizdat sovietico, 1956-1990, il Mulino, Bologna, 2013, 247-262.

[Diletta Bacci][11/06/2019]